I’m looking out at some much needed California rain, a sign of the season’s El Niño. You may have heard that this year’s is a “Godzilla” El Niño, already the strongest in recorded history (although we’ve only been keeping track since 1950), but what is El Niño, exactly?

The short version: it’s one phase of a cycle of wind and ocean circulation patterns that brings warmer waters to the west coast of the Americas, jumbling up weather across the globe. That means more rain for drought-stricken California and a warmer winter for the East Coast, but other places are drier than usual: Indonesia is seeing massive forest fires, and South Africa may face water shortages.

El Niño matters because these big weather changes can have big economic and social impacts: storm damage, floods, agricultural failures, fisheries crashes. We also need to understand El Niño because these large-scale climatic cycles and their interactions are crucial to our understanding of climate change, and conditions in El Niño can show us what’s to come in warmer years.

Okay, now the long version

There are many wonderful and interactive explanations of El Niño online, and I especially recommend clicking around on NOAA’s website.

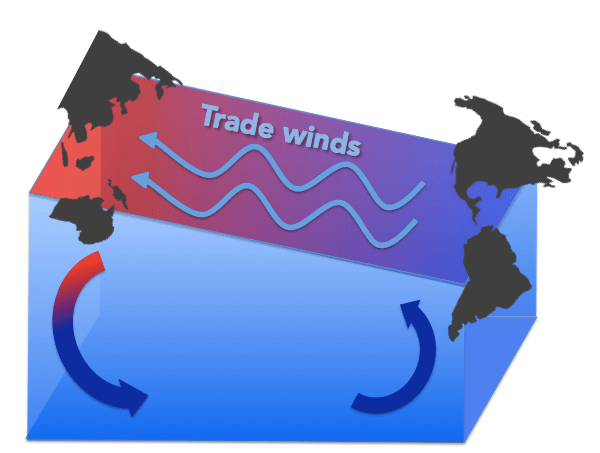

Under normal conditions, the trade winds blow east to west across the Pacific Ocean (basically hot air rising at the equator and then getting left behind as the earth rotates). They push water up by Asia and Australia, creating a slope. Think about blowing on a hot cup of coffee—the air pushes the coffee up against opposite side of the mug. The trade winds take warm surface waters and pile them up near Indonesia. Meanwhile, on the west coast of the Americas, cold, deep ocean water is pulled up to replace the water getting pushed away. This creates a massive circulation with warm downwelling in the western Pacific and cold upwelling in the eastern Pacific.

Under normal conditions, the trade winds drive circulation in the Pacific Ocean by pushing warm water up toward Asia and Australia. The piled up mass of water sinks down, while on the other side of the ocean, cold deep water is pulled up.

During El Niño, the trade winds weaken, for reasons we still don’t know. Just like when you stop blowing on your coffee and it levels out, warm water from the western Pacific flows back down toward the Americas.

All that warm water sloshing toward California means lots of warm, moist air, a recipe for rain. The flow of water toward the Americas (called a Kelvin wave) also disrupts the upwelling of cold water at the eastern Pacific, with big consequences for fisheries.

This is this week’s NOAA report of sea surface temperature anomaly (departures from average, with red representing warmer than usual and blue, cooler than usual). The warm (red) tongue by Peru is indicative of El Niño.

In fact, Peruvian fishermen who for centuries noticed changes in currents and the disappearance of their fish around Christmastime are credited with the name El Niño, Spanish for “the boy,” referring to the birth of baby Jesus. In the US, we tend to see the biggest effects between December and March. El Niño is part of a cycle that we complete every 3-7 years, and we call the opposite phenomenon (stronger winds, stronger upwelling, colder water) “La Niña,” the girl. The standard way we measure El Niño events, and thus make claims about a strong El Niño or a strongest ever El Niño, is by how much warmer than usual the ocean surface is in a standard region of the central Pacific.

We use the Niño 3.4 region (center, above) to measure El Niño events. If the sea surface temperature is 0.5°C warmer than average, it’s officially an El Niño. This November, the temperature in the 3.4 region was 2.35°C warmer than average Novembers! This is on par with the last huge El Niño we had, in 1997-98, when the November departure was 2.33°C.

What does this mean for fisheries?

The cold water upwelling off the coast of California and Peru brings up the nutrients that fall to the ocean floor, so those waters can support a huge amount of marine life. That’s why Peru is the second biggest fish exporter after China—they have extremely productive waters. During El Niño, with warmer, less nutritious waters and less upwelling, there isn’t enough food and fish populations crash. Anchovies, Peru’s staple, do best in cold nutrient-rich water, and El Niño-induced anchovy crashes are brutal to Peru’s economy. Fish also move closer inshore during El Niño to find colder water (this is why we’ve seen anchovies and unusual pelagic red crabs in Monterey Bay). This can be great for the small-scale fishermen, the guys I was working with, but it can also mean that the big boats sneak further inshore, creating competition and conflict. Big storms and flooding also wash freshwater and debris to coastal waters, which can kill fish and damage nets. Every El Niño event is different, and they bring complex, interacting effects, so it’s tough to figure out how to manage fisheries in the face of all this variability. Studying fisheries now can give us tools to deal with the next big El Niño, and make sure that management promotes the resilience of both the fish and the fishermen.

For more on El Niño, check out:

Daniel Swain’s California Weather Blog

Also, in light of the COP21 Paris talks/living on this planet, please read these excellent New York Times articles about climate change!