I’m now two weeks into a six-week scoping trip in Peru, traveling around, chatting to people, and trying to make sense of the small scale fisheries here. The idea behind this trip is that no matter how much you read about a place or system, it’s difficult to know what’s truly going on and what the relevant questions are without being there to see it, poke around, and talk to people. Also, just as with the fishermen in my survey, the fishers here know way more about this ecosystem and fishery than I do, and my main goal for this trip is to build those incredibly important trust relationships by getting to know some fishers here and listening to what they have to say.

I’ve been reading extensively about Peruvian fisheries and have some ideas of what I’m looking for, but I’m mostly keeping my eyes, ears, and mind open. The importance of these “kicking the tires” expeditions is widely acknowledged, but I’m still very lucky to have an advisor who is so supportive of such an endeavor!

Lima’s cliffed coastline

I’m also lucky to have the help and support of people that know the area and the fishermen. I’m working with Pro Delphinus, a Lima based non-profit that works with fishermen to reduce bycatch (accidental catch) of turtles, mammals, and birds. Co-coordinators Joanna Alfaro and Jeff Mangel have both worked closely with my advisor, so he was tickled when I came to him with their papers and outlined my plans for a Peru trip.

They’ve done wonderful and extensive work with small scale fishermen all over Peru, teaching them how to identify and free animals that get tangled in their nets, and providing them with deterrents like lights and sound-emitting pingers. The fishers are eager to participate because bycatch is a huge problem for them: a net lost to a whale entanglement costs over a thousand dollars to replace, money they don’t have.

I spent my first week in the Pro Delphinus office in Lima learning about the different projects they’re working on and the types of data they have. I’m extremely excited by what they’re working on. Peru’s fisheries are a big deal: it’s the world’s second largest producer of fish behind China, but the focus has been on the industrial anchovy fishery, nearly all of which is exported as fish meal and fish oil. The artisanal fisheries, largely neglected in the literature (except by Joanna and Jeff), are a major source of employment, and the fish is eaten here, representing over a quarter of Peru’s animal protein consumption. But Peru’s extraordinary productivity also means it’s a hotspot for other species, including endangered and/or charismatic ones like sea turtles and whales. Small scale fisheries in Peru are a huge source of mortality for these animals, comparable to industrial scale fisheries. What’s particularly impressive is that Pro Delphinus works with fishermen rather than against them, providing them with experimental solutions and soliciting and incorporating the fishers’ feedback.

Pro Delphinus also works with Tasa, one of the largest industrial fishing companies in Peru. We joined Tasa fishers and administrators in an annual philanthropy event, planting trees at a local school.

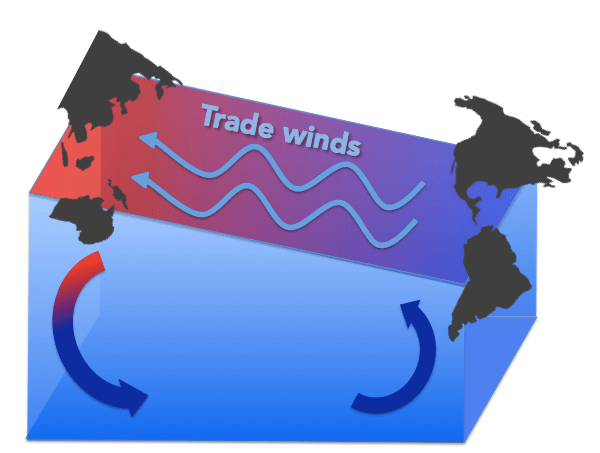

My original thoughts were to come here and get a better idea of the communities in which Pro Delphinus works. There’s scant literature on the social aspects of the artisanal fishery–who are these fishers? Have they always lived here or, as is increasingly common, are they migrants resorting to fishing following agricultural failures? What are the women doing? Peru is also dominated by El Niño (periodic El Niño-induced crashes in the Peruvian industrial anchovy fishery are the textbook example used to illustrate El Niño’s ecological impacts), and I’m interested in how this plays out ecologically and socially in the small scale fishery. How do both the ecosystem and the fishers adapt? It’s an El Niño year, so I thought this would be particularly relevant.

Unsurprisingly, from the moment I got here everything has been in flux, and I’m constantly learning new things and reevaluating my ideas. I couldn’t be happier to have this opportunity be flexible and open minded, and that I didn’t spend months preparing something specific but misguided. I think I’m even going to renege on my vow not to collect any data (“DON’T!” wailed an anthropologist I consulted before the trip. “Don’t even go in with a set list of questions! This should be like dating–just have a conversation!”). It turns out that Pro Delphinus has an upcoming project with Shellcatch, a San Francisco company, to give a sustainability certification (like the MSC certification I hope you look for in your seafood products; it’s similar to fair trade, but for being environmentally friendly) to some of their fishers in San José, a village in the north. Over the past few months I’ve become increasingly interested in certification programs like these, and what it means to eat sustainably in our global society (lengthy musings I’ll save for a future post).

I think it would be awesome to follow this project over the next few years and see what happens in the environment and in the community. I have an opportunity now, on this trip, to do a baseline assessment before anything has started, so I can have a basis for future comparison. I’ve written up a little survey that I hope to trot out in the upcoming weeks, and reached out people from Shellcatch, who have expressed interest in working with me, and possibly meeting if they make it down while I’m here. I’m trying not to let myself get too excited (COULD THIS BE MY THESIS?!) before I talk to Shellcatch, but this could be really fun and interesting if it pans out!

San José

I’m not, however, giving up my commitment to “people first, science second.” I spent the last week in San José chatting with the fishers and their families. It’s been so much to take in (compounded by my slowly returning high school Spanish skills), but I’ve had the wonderful and very patient help of Sergio and Astrid, of Pro Delphinus’s northern office. They first had a meeting with the fishers to distribute pingers and show videos of how to resuscitate tangled turtles, and I had the opportunity to give an introductory presentation about myself and my work, followed by a spirited question and answer session. I wasn’t expecting to cover such topics as the mechanical intricacies of the California purse seine fishery equipment usage or why sharks are important to ecosystems, but I think I did a passable job (the latter is more my area of expertise; I responded to the former with a lot of “yo no sé”).

During the meeting with fishermen, Sergio gave a presentation on the biology and ecology of sea turtles, and techniques for freeing them from fishing nets.

Over the next few days Sergio and Astrid took me around to fish markets, various government offices, and the fishers’ homes, where I got to informally ask them about their fishing and their environment, play with their children, and chat with their wives. Invariably the women would bring out some cake or plates of ceviche or a delicious fish dinner, and hours would go by as I mostly laughed vaguely at long fishing epics I only partially understood (so have I spent the majority of this week, alternating with furiously scribbling notes during jolting taxi rides). I’m blown away by the tremendous generosity of these families. They have running water and electricity for only a few hours each day, and yet wouldn’t hear of us ever eating in a restaurant. I’m grateful also that they’re already accustomed to talking with and trusting scientists–Pro Delphinus has done the hardest part for me through their years of wonderful and diligent work with these fishers.

We also briefly visited two other northern ports, Constante and Parachiques, and talked to people selling fish on the beach.

Once again, much is quite different–and much more complicated–than I expected. I have so much to think about: stories I see taking shape; inklings of ideas I’m excited to explore over the next month.

Santa Rosa fish market: “In Peru, the women work much harder than the men!”

I’m also taking a bit of time to wander along the Lima coastline, visit museums and galleries, eat unfamiliar fruits from sprawling markets, and partake in free outdoor salsa-Zumba. July isn’t Lima’s most photogenic month (it’s gray and clouded with sea mists every day, not unlike the California coast’s June gloom), but check out the photography page for some more pictures of my trip!

I loved the idea of designing a course and am always eager for opportunities to indoctrinate young minds with love of the oceans and interest in conservation, but I was hesitant—I don’t study the local Monterey Bay system, and it hardly made sense to drag undergrads down the coast to spout off barely-formed ideas about Peruvian fisheries. I’m enthusiastic about communication and outreach but have been feeling that I have nothing to communicate: I don’t have a thesis topic and don’t feel like an expert in anything yet. But I’m realizing that my perception of “expert” is skewed by my dazzling peers and professors, and I shouldn’t pass up opportunities to share.

I loved the idea of designing a course and am always eager for opportunities to indoctrinate young minds with love of the oceans and interest in conservation, but I was hesitant—I don’t study the local Monterey Bay system, and it hardly made sense to drag undergrads down the coast to spout off barely-formed ideas about Peruvian fisheries. I’m enthusiastic about communication and outreach but have been feeling that I have nothing to communicate: I don’t have a thesis topic and don’t feel like an expert in anything yet. But I’m realizing that my perception of “expert” is skewed by my dazzling peers and professors, and I shouldn’t pass up opportunities to share.

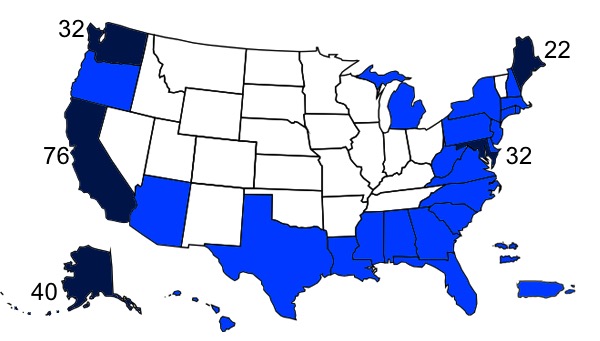

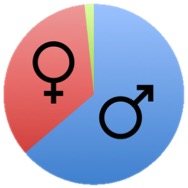

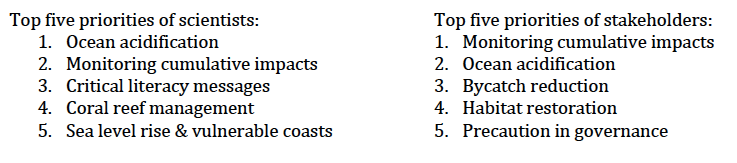

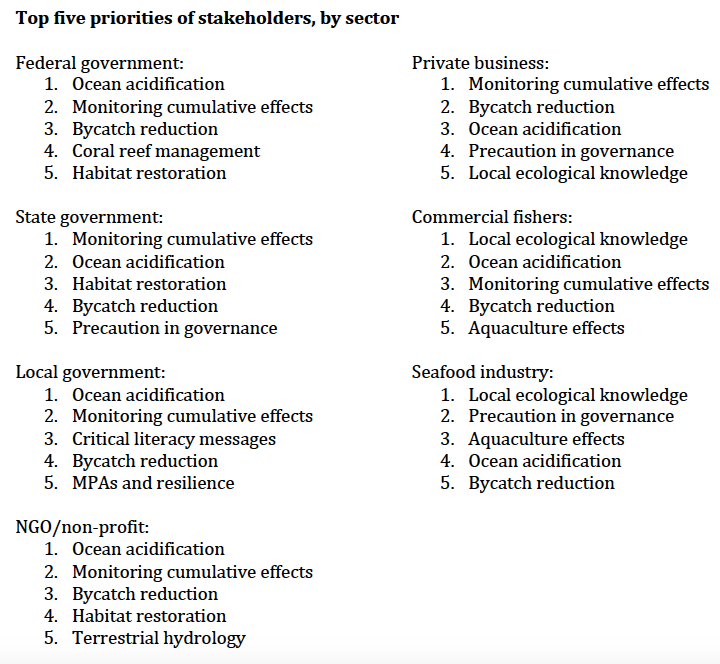

These results aren’t too surprising for anyone who has engaged in more applied or social science oriented work, but it’s exciting to have some numbers behind them. It looks like everyone is more or less on board about the big issues, but scientists could do a better job of focusing on policy-relevant issues related to fishing and habitat, and, most importantly, pay greater attention to what people who live and work with the oceans know through experience and observation. Once again, this requires a commitment to building trust and forming relationships, and it won’t happen overnight. After all the difficulty I had in getting fishermen to take the survey, I was amused to receive an email from a fisherman (in response to the report of results) expressing his disappointment that fishers were so underrepresented relative to government employees! I’m looking forward to continuing this analysis and improving my ability to engage stakeholders in relevant and useful research.

These results aren’t too surprising for anyone who has engaged in more applied or social science oriented work, but it’s exciting to have some numbers behind them. It looks like everyone is more or less on board about the big issues, but scientists could do a better job of focusing on policy-relevant issues related to fishing and habitat, and, most importantly, pay greater attention to what people who live and work with the oceans know through experience and observation. Once again, this requires a commitment to building trust and forming relationships, and it won’t happen overnight. After all the difficulty I had in getting fishermen to take the survey, I was amused to receive an email from a fisherman (in response to the report of results) expressing his disappointment that fishers were so underrepresented relative to government employees! I’m looking forward to continuing this analysis and improving my ability to engage stakeholders in relevant and useful research.